Egypt Ancient Currency

Currency In Ancient Egypt and Egyptian Money Usage Through History

The history of Egypt Ancient Currency is a direct consequence of the metamorphosis of one of the earliest and most significant civilizations throughout the history of mankind. In the beginning, there was no money, so the goods exchanged were for grain, livestock, or cloth. Until people learned, Metal weights and measures, including royal standards, were used to indicate the value of these products. At last, coins were invented in Egypt, and this was a turning point in most economies.

In the olden days, especially in ancient Egypt, coins were customarily manufactured from metal and engraved with the faces of deities, kings, and masters, which the coins were cast into the temples’ collections. Over the years, from the ancient through the Islamic and Ottoman periods, the types and forms of money present in Egypt changed. By the Victorian era or the 1800s, Muhammad Ali switched the base of the fiscal system, where the Egyptian pound was constructed.

Therefore, too, the history of money, or the development of the medium of exchange from barter to the so-called money, does not only signify the in economics but also the Egyptian context of participation in the financial market development since the Middle Ages.

1. Barter System In Ancient Egypt

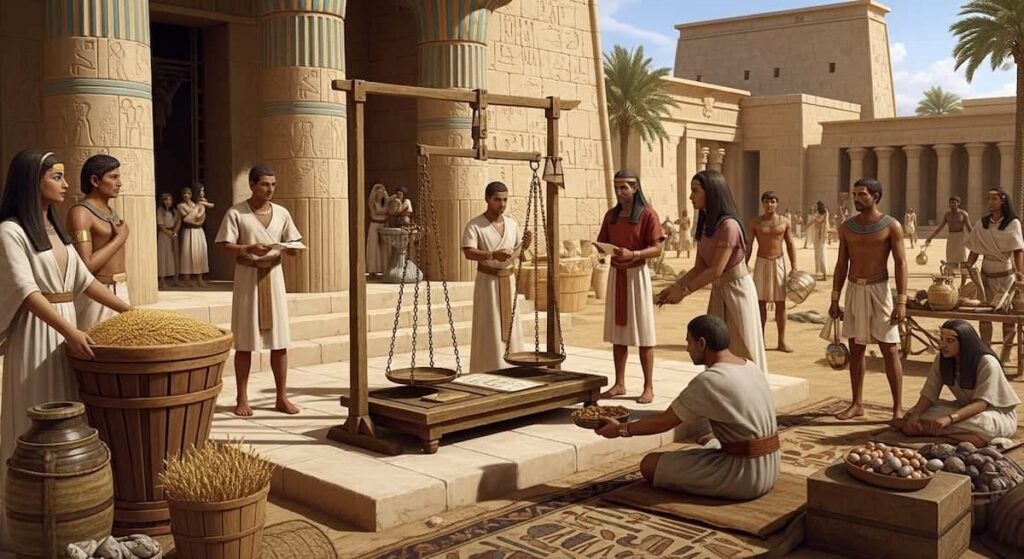

In the past, Egyptians did not use coins or some other standardized type of currency. Instead, they were forced to use trade as their main form of exchange. It is an old-fashioned way of doing business whereby people exchange goods and services simply because the party that wants one has what the other party wants in return. The goods and services are exchanged and not their monetary value.

For example, in barter settlements, grain, the most common type being wheat and millet, tended to be a very classical substance and even served as an old-fashioned style of ‘money’. If there was no grain, people could barter goods and services using domestic animals, particularly cattle. Other forms of trade include the exchange of beer, linen, bowls or cups, labor, and countless more. The farmers would do with the crops they have produced, for some agricultural implements, while the artisans would make art pieces in place of some food or resource. This method of trade, extraction, and production did work relatively well on a local scale.

However, the situation changed when trade became more common among numerous local regions and cultures. Predominantly, this change brought in the aspect of regulations within the trade. Where, in the absence of monetary values, there would often be agreements on the spot. Commercial registers and actual client right registers were used as well as contracts and “checks” for the settlements. This was the practice of bringing customers and determining purchase orders without the involvement of physical cash. All this was magic beauty that can be recreated and studied, otherwise known as the financial systems.

2. How the Barter and Trade System Worked in Ancient Egypt

The economic life of the ancient Egyptians predates the existence of coins or even money notes, with trade and barter forming the economic system in that age. As economic tools of exchange, the items used were the products themselves, based on such characteristics of a thing as its market value or use. A farmer, for example, would give an ear of wheat or barley, or cattle in return for an axe, a pot, or a piece of wooden fabric. This exchange system thrived mainly because the River Nile ran from city to city, enhancing logistics and trading.

Barter transactions included grains, cows, linen, cosmetics, paper, and alcohol. As Egypt was rich in culture and had commercial activities, it made it possible for the economy to bring in trade from its civilized neighbors, notably Sudan, Lebanon, Iraq, and others. In matters of import and export deals where the values involved are huge, the engagements were reduced to some writings or engraved on clay tablets, which is often very surprising for such economies.

Although not as refined as money, this primitive configuration of exchange was able to provide a clear track for the subsequent progress of the form of development. It is really amazing how some countries, such as Egypt, for example, managed to introduce organized economies without coins since ancient times.

3. Ancient Egyptian Currency Units and Money Symbols Explained

Before the introduction of coinage, the ancient Egyptians resorted to a carefully built collection of numbers and measures to the end of determine the worth of goods and materials. The most commonly accepted unit is the deben, something that has a weight of about ninety-three point three grams and is designed to determine the value of commodities or objects made of metals such as metals, silver and gold. The deben was sort of a benchmark currency for the traders and the administrators who were involved in the exchange of goods and services and foreign merchandise.

Also, two other remarkable units recognized during those ancient days include the kite and the sha’at. The kite was a lower value store of wealth typically designed for small amounts of precious metals; however, the majority of historians disagree on the existence, usage, and definition of the unit known as the sha’at, though it MIGHT have been, at its inception, about grain value or weight in fractions.

These methods of measurement were analogous to what we know to be money in modern day. Most transactions that occurred during those days were documented on papyrus or stone tablets that had inscriptions of symbols and hieroglyphics, which served as ancient forms of accounting systems. Wallerstein (1998) suggests that this economy, in which commodities played a central role, was important in guaranteeing fairness in trade, collections of taxes, and temples’ income.

4. What Is the Deben? Ancient Egypt’s Currency by Weight

Before coinage in the form of leather and metal rectangular plates, one of the important units of currency in ancient Egypt was the deben. It served as a general standard of weight equivalent to approximately 93.3 g and was employed in the calculation of the price for precious metals such as gold, silver, and copper. The principle of the deben was simple to establish a just valuation for the wares based on the amount of metals exchanged.

Thus, a tool or a piece of jewellery was priced at half a copper deben, whereas more expensive goods were measured in multiple silver debens. This made the deben the principal feature of Egypt’s proto-economic system. It was particularly notable for temple donations, taxes, and goods and services for highly lucrative economic activities.

Such transactions were duly registered by the Egyptian scribes on papyrus and tablets of solid material; hence the aside that put the deben, not only as a weight but as one that cemented the bond of trust, fairness, and orderliness in trade.

5. Sheat: The Mysterious Unit of Ancient Egyptian Currency

The sheat (also spelled sha’at) is one of the lesser-known measures adopted in the economic organization of ancient Egypt. Unlike with well-defined deben, the precise weight or nature of the sheat is still a matter of contention among historians and Egyptologists. The sheat could have served as a component weight unit specifically for small proportions of grain, gold, and silver. Nonetheless, others think that it was not the case and that it could have been related to religious or cluster-based economic practices, which are regional.

In comparison with deben, less has been written about the sheat, yet its role may have been more or less the same, where it helped the Egyptians in the appreciation of goods in a uniform manner. It was most likely supportive of the precoinage period in Egypt, especially the mode of trade within the markets among the local traders, more so in the lower-value transactions.

There are no available descriptions of how the sheat was used in Egypt, but its existence suggests that ancient Egyptians had native and complex economic structures that were able to guide some of the value handling systems, including food to precious metal exchange, having no coins.

6. Kite: The Smallest Ancient Egyptian Money Unit

In Ancient Egypt, a kite was one of the small denominations of the currency used by Egyptians. It was neither the main unit nor the biggest value; it was used for measuring finer qualities of gold and silver. Its function was to assess the deben, making it easier to calculate equivalent values during a transaction. For example, should a deben be 93.3 grams, the kite may be conceived of as one tenth or one twelfth of this amount, depending on the era and province.

The cantar was particularly convenient in trade places and small transactions that required only very minimal amounts of metal. In this way, it helped the Egyptians in facilitating trade with precision and justice, coupled with minor volumes.

The ancients, or the Egyptians, employed the response with the help of the cantar in such a way that the currency became modulated to allow moves to future coinage. It is also an indication of how deeply the sense of economic value and measurement was understood. Last but for sure not least, the kite may have been insubstantial, but it was an extremely important piece in the whole early trade and financial system of Egypt.

7. The Usage of Metals in Ancient Egyptian Coins and Trade

As the civilization of Egypt had developed, the use of rare metals was increasingly ingrained in its economic system. It was a very long period before the production of coins, when gold, silver, copper, and tin were considered as saving instruments. The measures of these precious metals were often in the form of mustel appearances, which the Egyptians used as the deben, with which they purchased suits of crops or animals or goods, the yellow goods as such, or pottery. Such weights of metals have reduced the necessity for silversmith guild commerce even for some big and ceremonial transactions.

Subsequently, stamped metal pieces also started being designed with some indicating marks, decreasing in amount and relative value. This began to instill the general notion of coins in an economy. The Egyptians knew some materials were more preferable than others and included gold at the top position, silver followed, then bronze, and lastly copper. Enhancement faced a challenge in dealing with other civilizations demanded heavy consideration on how to interact with a trading partner without insulting them due to cultural differences.

The adoption of metal for trade gave people the hope that they could set and maintain the value of barter goods; hence, it stopped the exploitation of people when it came to purchasing goods. It helped greatly in the development of real money during the ancient Egyptian era.

8. The Beginning of Coins in Ancient Egypt: From Barter to Minted Money

At the start of the money system in Ancient Egypt, a great leap was taken from barter and the use of metal for determining goods value to the establishment of money as it is understood today. Coinage became a matter of necessity for political and economic entities of ancient Egypt as the nature (operations) of these societies developed. Such an appreciation for the need for a ubiquitous and efficient medium of exchange resulted in the problem of Egypt’s coinage, which came at about 350 BC with the reign of Pharaoh Tachos. This particular coin was called “Nub Nefer,” which translates as “pure gold” or “good gold.”

Even though these Nub Nefer coins were not made for the general public, they were used by the Egyptian government, mostly for the payment of foreign soldiers in the employ of the state, especially Greek soldiers who were contracted to counter Persian invasions. These coins had pharaonic engraving and such, thus serving the dual purpose of carrying out trade and promoting the monarchy.

It is at this point that Egypt fully adopted coin-based commerce from what was conventionally known as metal trade, depending on the nature of the weight of such trade goods. The use of coins in early circumstances was ineffectual; however, it was the launching of a contemporary monetary system that emerged in the era of the Hellenistic and Roman.

9. Nub Nefer: The First Coin in Ancient Egyptian History

Known as Cleopatra’s Nub Nefer coin is perhaps the very first coin used in ancient Egypt. The coins date back to 350 BC and were created during the reign of Tachos as Pharaoh. The term is very reminiscent of “gold” or “good gold” based on both importance and meaning. The Nub Nefer was placed under rules imprinted with gold plates that were gold in colour, and were presented with inscriptions of their shapes.

However, the Nub Nefer circulated was virtually unknown and died out soon because it hurt the interests of both the Greeks and the Persians on the other side. They were usually employed to pay the Greek military men who had been appointed by the Egyptians to fight off the Persians.

This was characteristic because, quite obviously out of context of the normal arbitration bodies, this was how the two conflicting parties still carried the steadiest economic weight. The whole system of trading and international relations changed so as to increase its complexity, and when all these changes started taking place, Egypt too had to change its strategy.

There are only around 20 or so of the original blockers produced back in 1838; this gives them a unique value amongst enthusiasts of all things historical. It was at this interesting point in Egyptian history that the coined currency emerged as a different entity from weighed metal. The common currency was now stamped with an image of political significance and was worth a standard amount.

10. Other Currencies and Coins in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Symbols, and Royal Power

The Nub Nefer was made available, and the currency of Egypt had many stages that reflected the divine and political state of the country. Those “Egyptian pirate change” or “Egyptian coins” had a function other than trade, that of the sense of power and control, very often bearing the gods and animals, and powerful persons.

For example, there is a coin bearing the image of the deity Khepri, who is most frequently depicted as a Scarabaeus sacer. This beetle was associated with the birth of the dead man and the new, promising sun: the currency was an object of divine protection. As for another coin, it featured a sheep, which could be Ammun-Ra’s, the most intense sun deity, or Khnum’s, the God of creation. Such objects enhanced trade and wealth, but also, they particularly enhanced the integration of religious aspects into the exchange of goods.

It is also said that even Queen Cleopatra created bronze coins of her own. The obverse featured her portrait while the reverse featured a lightning bolt and an eagle linking her to power and divine protection. Purchasing this particular series of coins was like endorsing her reign and expressing women’s views in the whole of Egypt and beyond.

-

Pharaonic Coinage of the God Khepri

Coins that were coined in the most recent stages of ancient Egyptian civilization were made bearing religious engravings and markings, among the most common ones being Khepri, a god represented as a scarab-headed man of nature, who is also the god of rebirth and the rising sun. Apart from just being his image, which was usually engraved on the coins as a beetle scarab, the figure they represented symbolized transformation, rebirth, and divine energy. It has to be mentioned that the society of Egypt understood that a coin is not merely a means of exchange; it is a religious symbol and strengthens the belief in the power and holiness of the king.

Such an example of the practice of Khepri on the coins only shows how, in the monetary world in ancient Egypt, money, too, had its share of function divided between the economic and religious sectors. Leaders of the past who marked popular deities on the coinage employed spirituality in a way that suggested and reminded the public that those leaders were chosen as appointed rulers. Even though these coins were not put into wide circulation, the coins bearing the likeness of a Khepri’s symbol began the process of development of the conviction that there was a way to invest more in money other than material profit; money could inhabit and move beyond the confines of anything that was deemed to have value, in other words, any meaning, ideology, even religious hope within the country and without its boundaries.

-

Pharaonic Coinage of the Ram: Amun-Ra and Khnum Symbolism

In the time of ancient Egyptian coins, the representation of the ram icon was so important that great attention was given and very powerful deities such as Amun-Ra, the deities king, and the sun god, Amon. This deity and many others, like the Heka Ghusen, the desert God or Holy Mother, and the great creator God associated with the Nile and God Kunka, amongst others, were depicted in the ancient Egyptian coinage. Bills bearing the image of the ram or complete rams were very few, as they were mostly meant for show or large-scale exchanges that included religious institutions as well as royal households.

Despite all their complexity, however, these coins were, first and foremost, instruments of finance enabling one business entity to pay or charge another for goods or services they have received or rendered, thus the economy or let alone how much they earn less spend without these coins.

However, a ram, an animal that was held in high esteem and was worshipped before being held as representative of a demi-god, a characteristic that was accepted by most of the Asian Negro ethnic groups, including a large section of the world freshwater gay communities, was also a supreme symbol of fecundity, the ability to perform. Such sovereignty was wished as it served as a tangible exemplar to any ruler trying primarily to re-cement the historical relations with the religions.

Frequently applied to the front and rear sides of them, the ram would mediate the pharaoh’s image as an ideal ruler and the real ruler on the throne. through the sign of his dress, and as will be analyzed, other political markers through his coins.

11. Cleopatra’s Pharaonic Coins: The Queen on Bronze Currency

Cleopatra the Seventh, also known as Cleopatra the Last, was the reigning pharaoh in Egypt. She kept the spirit of branding and came up with her unique brand of money. Cleopatra came up with a series of coins made from copper, which featured her image on one side and the image of an eagle perched on a thunderbolt on the other. The eagle and the lightning bolt were significant as they were phallic symbols of power, kingship, and divine representation, and especially sex and the goddess-like thunderbolt to a directive gust of male energy and male courage.

And her coins were not a matter of another free economic form but rather very political from the beginning. In this respect, she defies male chutzpah in the ancient world. This male dominated the growth of his subject through his absolutism and was called a man in his time and space. This is a common trait of Bronze-Age and late-Iron Age empires, as well as the associated symbolism of being ruled by a monarch versus a despot.

Her coins were used extensively, serving two main purposes in different sectors all across eastern and western lands, respectively, Egypt, promoting her influence, and wielding power as an independent ruler. The removal of the separate parts of the verse on the same coin was described as another quite effective strategy of the ruler.

For her coins, Cleopatra made several motivations important to both Greek and Egyptian society. Cleopatra’s coins were not only coins, but rather a war of propaganda waged by the head of the state without military action, illustrating the power of the ruler to advance his or her regime with the aid of currency by molding preference and domination.

12. The Evolution of Currency in Egypt and the Influence of Roman Coins

How money was used in Egypt evolved significantly through the centuries. Barter and weighed metals as forms of trading paved the way to the use of minted coins. It was in this regard that the Ptolemaic and Roman eras changed the trend with dense adoption of the latter, especially considering coins were widely used in the markets of the city and throughout the Roman Empire. Ever since the introduction of the very first actual coinage made during the reign of Alexander the Great, widely circulated coins also showed his portrait among many others. Concerning Egypt, these were the days in history when the exchange of money through the use of silver coins became popular.

With the conquest of Egypt by the Romans in 30 BC, the official units of coinage were significantly in use. These Roman coins were made of gold, silver, and bronze, where on the obverse were emperors and Egyptian gods or Egyptian symbols on the reverse in most. This fashion double culturing explains how Egypt looked under the Romans. These kinds of coins also let in the economics of the Egyptian region with that of the Roman world by replacing the traditional methods and fostering the growth of a market economy that would last for a long time.

13. Egyptian Currency and Value During Ancient Islamic Civilization

With the advent of Islam in Egypt during the 7th century CE, the existing currency practices underwent radical changes. When Islam spread to Egypt during the reign of Caliph Omar ibn Al-Khattab, the first officially Islamic coins that were used and produced in Egypt were silver dirhams. These silver dirhams followed the Persian coinage in terms of weight, form, denomination, legends, and even mintplaces, notably Al-Kufa, which was known as Al-Mada’in at that time. They were initially borrowed with foreign designs and Persian inscriptions, but gradually over the next couple of years developed exclusively into fully Islamic currency.

By the time of Caliph Uthman ibn Affan and later Muawiyah ibn Abi Sufyan, coins featured Arabic inscriptions like “God is Great” and other religious phrases to distinguish Islamic identity. The most significant reform was made in 65 AH / 685 AD through Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, whose new gold dinars and silver dirhams (which both preceded reformation) had a fixed weight and included Islamic information, history, or religious science inscribed on one or both faces of the coins. These coins did not allow the use of Roman currency and had a more unified Islamic government that complemented the administrative culture.

The economy of Egypt evolved rapidly, and within a short span, there was wide usage of coins in governance functions such as taxation and trade. Islamic currency in Egypt did not merely signify economic worth, but also religious authority and political power.

14. Egyptian Currencies in Muhammad Ali’s Reign: The Birth of the Modern Pound

The emergence and activities of one of the Khedives in Egypt at the beginning of the modern century signified the profound changes taking place in the country’s state structure. The ruler, obsessed with reform, justified to himself the reorganization of the old monetary system as necessary for building a new industrial and administrative complex, and thus introduced a completely new system of currency.

In that context, the principal unit of account was the Egyptian riyal, a silver coin weighing approximately five grams and divided into twenty parts, each called a piaster.

Then came the Egyptian pound (geneih), made from pure gold, valued at 100 piasters, and used on many formal occasions. The expression “goldsmith” or “social” type of coins no longer fits the changing reality. This development worked to transform traditional Egyptian monetary culture, adapting it to the new Western system. The terminology of currencies was also standardized.

By the year 1899, the National Bank of Egypt introduced the first banknotes, initiating a gold-pegged currency system. Egypt’s modern money history effectively begins with Muhammad Ali Pasha, under whose rule, treasury policy became a strong instrument of state power.

15. From Khedives to Kings: Egypt’s Royal Coinage from Ismail to Farouk

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the currency in Egypt underwent further transformations during the rulership of Khedive Ismail, King Fuad I, and King Farouk I. Under Khedive Ismail, copper coins were issued bearing the name of Sultan Abdul Aziz, signifying Egypt’s continuing ties to the Ottoman Empire. Later, during the administration of Khedive Tawfiq, the Egyptian pound was formally introduced, divided into 100 piasters, with smaller units such as the millieme.

In 1922, following the declaration of Egypt’s independence, King Fuad I authorized the minting of gold coins, produced in London. These coins bore his portrait and the inscription: “Fuad I, King of Egypt.” By 1937, during the reign of King Farouk, silver coins were issued in denominations of 2, 5, 10, and 20 piasters, also featuring the king’s effigy.

These coins serve as historical benchmarks of national identity, offering both numismatists and the public a glimpse into the pride and statehood of the Egyptian people, symbolizing a shift from colonial dependency to sovereign rule.

16. Conclusion: The Legacy of Ancient Egyptian Currency Through Time

The use of currency in Egypt has progressed through several distinct phases from primitive barter systems to the adoption of sophisticated coinage and paper money. In ancient Egyptian society, trade initially relied on essential commodities exchanged through barter, later evolving into weight-based units such as the deben, kite, and sheat, which were used to assess the value of precious metals.

Early forms of coinage began with stamped marks on metal, seen in rare examples like the Nub Nefer coin. Over time, these evolved into more structured systems, transitioning through Pharaonic, Greek, Roman, and later Islamic coins. The historical record of these coins reflects a deeper narrative—coins were not merely economic tools, but symbols of power, authority, religious influence, and ritual significance.

Throughout history, Egypt’s monetary system adapted to reflect the political climate and market demands of each era. Currency consistently served as a mechanism of control, a medium for spreading ideologies, and a marker of political legitimacy.

Even modern Egyptian money retains echoes of this ancient lineage. Its chronological evolution highlights Egypt’s enduring contribution to global financial systems and confirms its significant role in the development of human civilization.